As Union forces began their northward march through Georgia in 1864, the Confederate Army grew concerned about the potential threat of liberated prisoners from the stockades at Macon and Andersonville. The prisoners were quickly evacuated by train and held under guard in temporary quarters at Charleston until another facility could be constructed. The Confederacy needed and inland location that was accessible by train and out of harm’s way. The site they selected was Florence.

In early Summer of 1864, a workforce of nearly 1,000 slaves from local plantations began clearing approximately 15 acres of land near Jeffries Creek to build the Civil War prison that became known as the Florence Stockade. Land and slave labor for the stockade’s construction were donated by Dr. James H. Jarrott. The design of the Florence Stockade was modeled after the prison at Andersonville. Heavy upright timbers enclosed a rectangular field, 1,400 feet long and 725 feet wide. Pye Branch, a small tributary of Jeffries Creek, divided the stockades’s interior. An earthen rampart against the outer wall served as a walkway for guards, and a deep trench beyond the rampart prevented prisoners from tunneling out.

Prisoners began arriving at the unfinished stockade by train in September, 1864. By the end of October, over 13,00 captured Union men from every northern state were confined at Florence. Food, clothing, and shelter were in short supply. Many prisoners lived together in square pits dug into the ground. Others improvised huts made of sticks, layers of pine straw and clay. Their conditions were so poor that many Florence citizens donated food and clothing and and volunteered as medical assistants in the stockade’s hospital.

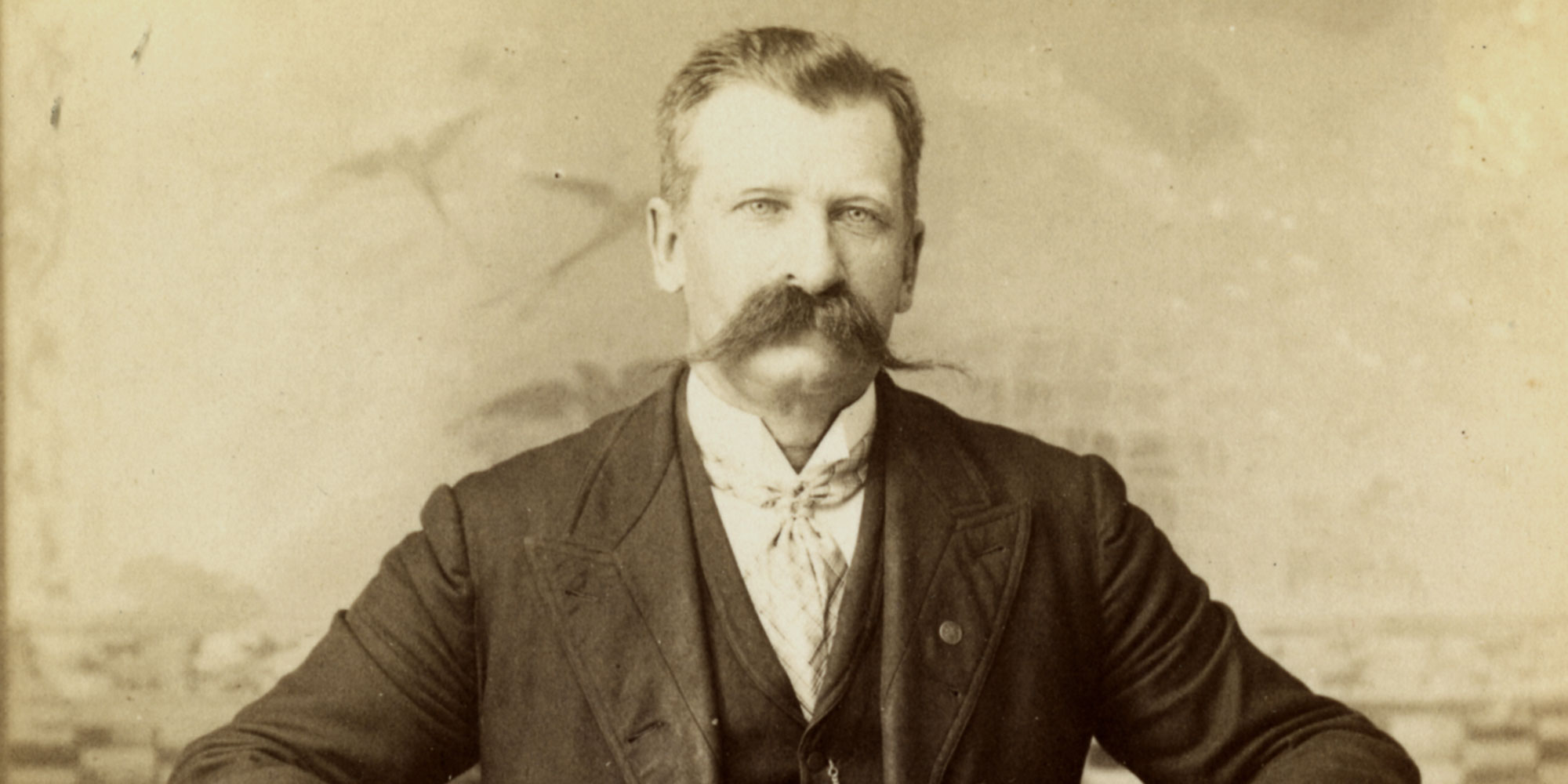

John Wales January, a 19 year-old soldier enlisted in Company B of the 14th Illinois Cavalry, had been captured when Confederate calvary overpowered Union forces at the Battle of Hillsboro (or Sunshine Creek) in July of 1864. January’s personal account indicates the severity of the destitute conditions at the Florence Stockade.

“I was captured by six rebel soldiers, sent to Andersonville, and there kept until the fall of Atlanta made it necessary for us to be removed to prevent falling in the hands of the Union forces. I was taken to Charleston, S.C., with others, and placed by the enemy under fire of our soldiers and gun-boats; remained here ten days and was taken to Florence, S.C., where we passed the winter of ’64-5, and on or about February 15th I was stricken down by an attack of swamp-fever, and for three weeks I remained in a delirious condition; the fever abated and reason returned.

I soon learned from the surgeon, after a hasty examination, that I was victim of scurvy and gangrene and was removed to the gangrene hospital. My feet and ankles, five inches above the joints presented a livid, lifeless appearance, and soon the flesh began to slough off, and the surgeon, with a brutal oath, said I would soon die. But I was determined to live, and begged him to cut my feet off; telling him if he would do that I could live. He still refused; and, believing that my life depended on the removal of my feet, I secured an old pocket-knife (I have it now in my possession) and cut through the decaying flesh and severed the tendons. The feet were unjointed, leaving the bones protruding without a covering of flesh for five inches.

At the close of the war I was taken by the rebs to our lines at Wilmington, N.C., in April 1865, and when weighed learned that I had been reduced from 165 pounds (my weight when captured) to forty-five pounds. Every one of the Union surgeons who saw me then said I could not live; but, contrary to this belief, I did, and improved. Six weeks after release, while on a boat enroute to New York, the bones of my right limb broke off at the end of the flesh. Six weeks later, while in the hospital on David’s Island, those of my left foot had become necrosid and broke off similarly. One year after my release I was just able to sit up in bed, and was discharged. Twelve years after my release my limbs healed over, and strange to relate, no amputation has ever been performed upon them save the one I performed in prison…”

Photo of J. W. January shortly after release from the Florence Stockade. Image courtesy of Minonk Talk.

Photo of J. W. January c. 1880. Image courtesy of Boston Medical Library.

January lived into his 60s. In fact he became well-known for the account. Newspapers articles and medical journals alike recounted the tale of his infection, self amputation and unlikely survival while imprisoned in the Florence Stockade.

There does exist an alternate account of January’s story originating from Valentine Meyers, an army nurse who served at the Florence Stockade. According to an article published in 1906, Meyers recalled that doctors in the Stockade hospital did in fact amputate January’s feet upon a second inspection of the prisoner’s serious infection. Meyers claimed that the amputation came quite easily to the army doctors given the advanced state of gangrene infection in the prisoner’s feet.

If you would like to learn more about J. W. January’s experience in the Florence Stockade, check out the following sources used to help author this post:

Books:

Village to City Florence, South Carolina 1853 – 1893 by Eugene N. Zeigler Jr.

Web Resources:

Unknown, “Artificial limbs removed,” Center for the History of Medicine: OnView, accessed December 1, 2015.

“John W. January – Civil War Veteran,” minonktalk.com/jjanuary.htm